By Han Ming Xuan (with thanks to Dr Jade)

A note about life’s stressors

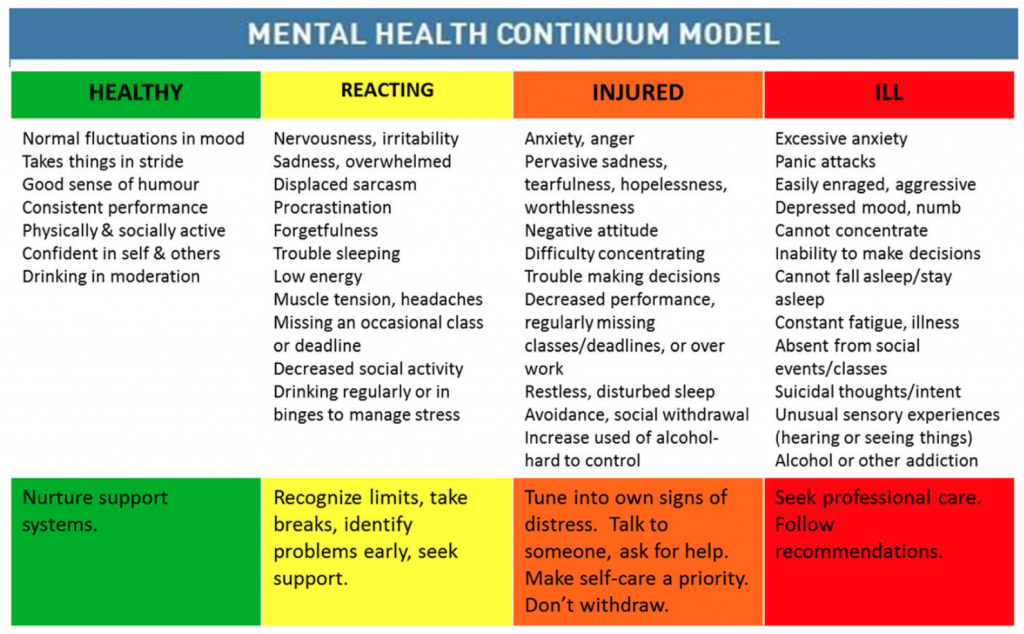

As with any stressor in life, different people respond in different ways. It is vital to recognise that psychological trauma is something that is relative, and never comparative. Can we say that what we went through in our life is worse than what others have had to endure? Well we are entitled to a subjective opinion, but we are in no position to trivialise another’s experiences if we didn’t lead their life. Which leads us to addressing the general perception of mental health and mental illness – each and every one of us fluctuates along what well-being experts call the Mental Health Continuum. This is a scale created by the Canadian Armed Forces to explain how people cope, as shown in Figure 1. [1]

Figure 1: Mental Health Continuum Model [1]

Mental health cannot be simplified to a yes/no, switch on/switch off sort of problem. As represented by the four colours in the figure, we are all fluctuating in between stages at any point in our life, subject to the onslaught of stressors varying in magnitude.

To a paramedic or emergency physician who takes charge of countless resuscitations every day, a single case of cardiac arrest might not necessarily have as great a psychological impact on the individual as compared to a bystander or next-of-kin witnessing the same scenario taking place.

No matter who we are and what role we play, it is important to be in-tune with our emotions. Most of the time when we drift to the “reacting” stage, we adopt self-care strategies to destress – evening runs, bitching with friends, that luxurious staycation, or some alone time. And most of the time these strategies help with coping. However, sometimes the stressor might just be a tad too overwhelming, pushing us to the “injured” stage. Recognising that we are not okay and that we need someone to talk to is a sign of courage, never weakness. It could be beneficial to speak with someone like a life coach, therapist or psychiatrist depending on the level of fear and anxiety.

Care strategies for yourself and others

The best care strategies are as good as the ones that are most suitable for you. Different things work for different people. Dr Jade teaches us that therapy comes in many forms. For me, sometimes a stroll alone on a random boardwalk is great and sometimes I just want to have a darn good nightcap. For Dr Jade, Marion and Marcel, immersion in the world of art is perfect.

For others, the coping strategy could be a mean scalp massage, pottery classes, cooking or art jamming. What’s most important is the need to be able to recognise when we need to seek help, or to use the common analogy: when we need to empty our bucket before it overflows.

References

[1] Chen SP, Chang WP, Stuart H. Self-reflection and screening mental health on Canadian campuses: validation of the mental health continuum model. BMC psychology. 2020 Dec;8(1):1-8.

Motivation behind this series

Starting out as a paramedic trainee got me thinking hard about psychological well-being. For too long topics like these are shunned by lay people and healthcare professionals within and outside the fields of medicine because for some reason, being in such professions, we somehow are expected to “act the part” in the face of trauma and adversity: suck it up and move on! No denying that we are all resilient and tough individuals but a culture of not speaking up trivialises the importance of mental health.

Speaking to Dr. Jade led me to realise that even at her level of seniority, experience and standing, mindfulness and well-being are on the top of her list even as a senior paediatric emergency specialist. She inspires so many and she paves the way for more open conversations about well-being in healthcare and beyond. My gratitude goes to Dr. Jade for her unwavering support and guidance throughout the conceptualisation and writing of this series.

1 Comment

Leave your reply.